On Saturday I headed to Kanchanaburi for a short break. It’s a journey that should have taken, perhaps three hours. However, the following Tuesday was a national holiday, so every man and his dog had decided to take Monday off and have an extended break. The traffic was horrendous. And to make things worse, on one road a truck had hit something and turned on its side shedding its load of vast sacks full of carbon on the carriageway. I sat for a full hour in traffic just inching forward. And then it got dark, so traffic slowed even further. I eventually reached Kanchanaburi well after 8 p.m., having spent seven hours behind the wheel. Now, Kanchanaburi is famous for its war graves, the death railway and the Bridge over the River Kwai (even though the river isn’t the Kwai, but the Kwae – rhymes with grey) – but I’d been there, done that and got the T-shirt. I was here for Khmer temples, tigers and majestic scenery.

Meuang Singh

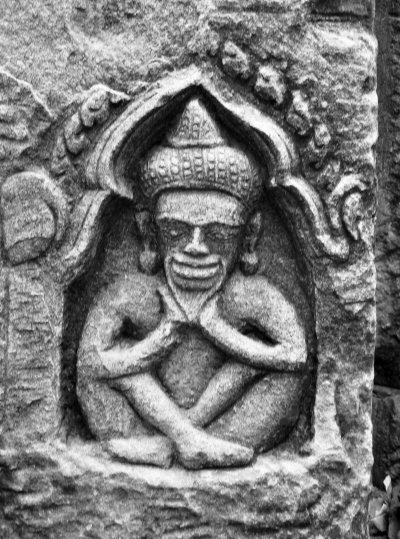

On Sunday I headed out of town to Meuang Singh (literally Lion City), a 13th century outpost of the mighty Angkor empire. Unlike the Khmer temples I visited in the north east, the buildings here are made of laterite, rather than of stone, and have no fine carvings. Rather, they were covered in stucco, of which only fragments remain. Furthermore, the temples were dedicated to Mahayana Buddhist Bodhisattvas, rather than to Hindu gods. Most of the buildings here are little more than piles of rubble, apart from one temple, with its central prasat. (Originally there were eight smaller, prasats around the central one, but these no longer stand.)

In the inner sanctuary stands a figure of the Avelokiteshvara, the Bodhisattva of compassion.

The inner sanctuary is surrounded by a gallery with a barrel-vaulted roof.

Afterwards I headed to another place with a feline association: the Tiger Temple.

Tiger Temple

The Tiger Temple is known for its tigers which visitors can get up close and personal with tigers – no bars or moats – and have their photo taken.

There are different versions of exactly how the temple started to take in tigers, but one version is that two orphan tiger cubs (their mother having been killed by hunters) were bought by a wealth man in Bangkok. The cubs fell sick, and their owner ordered them killed and mounted. However, the taxidermist couldn’t go through with this, and they were offered to the abbot. Buddhism teaches compassion for all life, so the abbot felt compelled to take them in, even though he knew nothing about caring for tigers. He nursed the cubs back to health. News of this spread, and he was offered more tigers – orphans and unwanted pets. He took them all in. They thrived and had cubs of their own.

Looking after tigers is an expensive business, so the temple started charging visitors to meet the tigers. And now the temple is one of the major tourist attractions in the Kanchanaburi area.

At 1 p.m. every day the tigers are led from their cages to a steep-sided canyon where they lie docilely in the sun attended by yellow-shirted volunteers.

I arrived shortly before 1 p.m., and there was a large crowd of tourists which had arrived in buses and minivans. I waited to let them go ahead. I saw a monk carefully wash out baby bottles into which he scooped powdered milk. He then took a teat and bit the end off with his teeth. Meanwhile a young temple boy, perhaps 6 years old, was in a cage with a young tiger. He wanted to get the tiger out of its water trough, so he grabbed it by the tail and pulled. The tiger quickly turned its head and snarled. The boy backed off, but the monk told him not to worry, so the boy threw a plastic ball, and the tiger was soon distracted.

In the canyon the visitors are kept behind a rope (not much protection should a tiger go ape) and are led forward, one by one, to have their photograph taken with a selection of recumbent tigers. Both large:

and small:

(And for an extra 1,000 Baht one can have a photo with a tiger’s head on one’s lap.)

An unanswered question is why the tigers are so placid. The temple says it’s because they have been hand-reared from a young age, and have just been fed. Some (but without any evidence) say that the tigers are kept drugged. And others point out that the tigers are fed a special herbal drink which the abbot claims is to support their good health, but others suggest may be a soporific.

Then there’s the emphasis on money – the entry fee, the souvenirs, the expensive “special photo”. The abbot is concerned that the current tigers can never be released into the wild – they simply don’t have the necessary survival skills. The temple has bought a large tract of land which it is in the process of converting into an “island” on which tigers will be able to roam freely without interference from man. The hope is that the next generation of tigers will be able to be released into the wild.

I’d like to believe that the abbot is genuine. Certainly, the temple attracts a good number of Thai volunteers who show the tigers off. The temple attracts large donations from local people, too. Surely the good opinion of these people is worth more than that of casual tourists passing through.

Sai Yok

The area to the north west of Kanchanaburi is dotted with waterfalls. Of these the most famous are the Erawan falls, which I saw almost 5 years ago. This time I wanted to visit Sai Yok National Park, which has two waterfalls, Sai Yok Yai (large) and Sai Yok Noy (small), which are about 30 km apart. Big is better, so it’s to Sai Yok Yai that I headed. The park is in thick tropical jungle, and one drives through a cathedral of trees to reach the falls.

The falls are where a tributary joins the main river. To see them properly one has to cross the river by a rickety wooden suspension bridge which swings with each step. (London, eat your heart out – Thailand had wobbly bridges long before any across the Thames.)

The falls, however, when you see them, are hardly that impressive:

Still, it was a pleasant diversion, and very tranquil.

Some of the local wildlife, however, was to be avoided:

[295]

Recent Comments